News

MIKA IMAI: FRAMING LGBTQ/DEAF INTERSECTIONALITY Film Trailers & Mika Imai Interview from LGBTER

Posted on September 15, 2022

The UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Sexual Culture will host the filmmaker Mika Imai from Japan, the creator of the LGBTQ/Deaf films Ginger and Honey Milk and Until Rainbow Dawn. Imai will screen the two films and participate in Q&A sessions. The event will take place on September 26, 2022 at 370 Dwinelle Hall on the UC Berkeley campus. Ginger and Honey Milk will screen at the 12:00 to 14:00 session and Until Rainbow Dawn will screen at the 18:00 to 20:30 session. Please check the CSSC EVENTS page for more details.

Ginger and Honey Milk Trailer

Until Rainbow Dawn Trailer

Mika Imai LGBTER interview: I live in a visual world and movies are my life—so I keep creating

Translated excerpts from the 2019 LGBter interview with Mika Imai (今井ミカ) available in Japanese on the LGBTER website (by Mayuko Sunagawa) with modifications based on reference to Mika Imai’s website (English translation by Johnny George)

From an early age Imai has been immersed in filmmaking, resulting in several films that have received an enthusiastic response from a variety of audiences. Imai’s earliest work relies upon visual action and Japanese Sign Language (JSL) as the vessels for expression. Imai’s first film to incorporate a soundtrack, Until Rainbow Dawn, debuted in 2019 at the 27th Rainbow Reel Tokyo International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival and featured at the 29th Hong Kong Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. Imai’s latest feature Ginger and Honey Milk premiered at the 3rd Tokyo Deaf International Film Festival in 2021.

Imai produces a variety of entertainment such as the comedian duo “Deaf W”, and media such as “The Sign Language Picture Book of Living Creatures”, and in addition does video production work including commercials. Imai’s Youtube commercial for the Japan Foundation Phone relay service, “Never Give Up” premiered in March 2022 and in one month received over two million views.

Imai was born in Gunma prefecture, Japan and grew up with Japanese Sign Language (JSL) and Japanese. Imai studied in the Wako University Faculty of Expression with a focus on video production. In order to learn more about sign languages Imai became a research student in the Japan Foundation Asia Pacific Sign language linguistics dissemination project in 2011. Imai loves cats and coffee.

1. Sign language as the means of communication

Imai’s parents and younger brother are Deaf. “My family is Deaf, so using sign language is natural. When I was little, our family would frequently drive to a river or a place with natural surroundings and campout, barbecue and then go to bathe in the hot springs. My dad loved to fish and would take me along; once I caught a fish with my bare hands!” Imai’s father had a caretaker side and a friendly side that would listen closely to personal concerns. Imai’s mother had lots of patience. “For my mom Japanese was a second language, so she had difficulty understanding Japanese at the Deaf school’s PTA meetings and building relationships with other parents and educators, but she participated without complaint.”

“It wasn’t until I attended a sporting event in the 1st grade that I realized that my family was different. We always used sign language, so other families did not communicate much with us since we did not share a common language. I became surrounded by people who pitied us for lacking the ability to hear but I believed that my family who could talk about anything was truly happy, and I never wished for hearing.”

When starting preschool, neither the teachers nor the students knew sign language. Imai was typically alone and frustrated with the inability to communicate. After preschool Imai started kindergarten in a Deaf school. In the Deaf school students primarily had to communicate through lip reading because the school forbid sign language. “At that time the educators believed that students using sign language would undermine their comprehension of Japanese. Up until then I had never encountered lip-reading, so found the notion very confusing. After school we would have one-on-one lip reading lessons with the teachers. We would look at the lip shapes and try to pronounce each sound. We would not only practice mouth shapes, but would put our hands in front of the teacher’s mouth and try to feel the air expelled durning pronunciation. For nasal sounds such as ‘na’ we would touch the nose in order to feel the sound reverberate. We would observe and repeat sounds over and over again. It was incredibly frustrating. No matter how hard we tried we could not successfully produce the sounds.”

“My family and friends used sign language so we could live our lives and function in the school social community smoothly. Through sign language we developed our critical thinking, vocabulary and communication skills. If I had not used sign language I would not be the person I am today.”

2. I hate skirts: Being in a Deaf School

After kindergarten Imai continued to go on to the Deaf elementary school. One day, with Imai’s mother and paternal grandmother they looked for something to wear for the elementary school entrance ceremony. “They thought I should wear a skirt, but I thought `do I really have to wear a skirt?’ Although I really hated the idea, when I tried one on they said it looked very cute, so I did not say anything despite hating it.” Imai wanted to see them smile and not cause strife so simply complied; however, after looking at the ceremony photos Imai thought that wearing the skirt looked strange. After entering elementary school Imai usually wore pants and avoided typically feminine clothing. Imai did not particularly prefer male clothing but wanted to wear what felt right. Imai’s feelings about what to wear has remained the same ever since. “It’s really odd to designate clothes by gender such as pants for men or skirts for women.”

“The first person I ever had a crush on was a very attractive female lip-reading instructor. I really hated lip-reading training but with this teacher it was very fun and I tried my best!” (laughs) “It was the first time I ever had an attraction to someone.” Imai was rarely attracted to classmates and typically found older women attractive but could never tell anyone. There were only eight students in Imai’s grade level at the Deaf school, so from 1st grade until the end of high school the same eight classmates studied together. “We had a really close relationship like siblings so could argue and interact frankly. Older and younger students and teachers were all nearly the same because the Deaf school was a very small world.”

3. Discomfort with femininity

From third grade on Imai would increasingly hear friends say, “I like this guy,” or “so and so is so cool!” The girls had an interest in boys but Imai never developed the same type of feeling. “I wasn’t interested in boys, I liked girls.” Imai never communicated such feelings to anyone because it felt taboo. “Even in elementary school the words ‘lesbian’ and ‘homo’ were familiar to students in sign language. We learned the language from adults in the Deaf community. The guys would sign ‘lez’ or ‘homo’ in derogatory ways, so I thought that I could never admit my attraction to females. Whenever someone asked if there was someone I liked, I would name a popular guy in class.”

Progressing through elementary school there became more topics that Imai could not discuss with friends. “I despised conversations based on ‘That girl is beautiful, isn’t she?’ or ‘that girl is so sophisticated, isn’t she?’ or ‘He’s so cool!’ I felt uncomfortable participating in such conversations. If I did not respond others might wonder why. In that small environment eventually rumors might have spread about me and other students would have looked down on me. I had no alternative school if I fell out of favor with my classmates.”

Imai’s body eventually started changing. Peers started wearing and recommending bras and Imai’s parents recommended wearing a bra too. “I didn’t believe that it was necessary. I felt that my expanding breasts signaled getting fat, not a maturing body. I didn’t worry about the growth of my breasts and resisted wearing a bra for a long time. By the eight grade my period had started. I really hated my period––my breasts swelled and blood emerged. I eventually accepted the need to wear a bra.”

4. Finding a confidant

From junior high school conversations about dating became increasingly frequent. “I was supposed to have a boyfriend but was attracted to my music teacher, who was very beautiful and had a fascinating, mysterious air. I persistently tried in sign language to flatter the teacher. Everyone would enjoy talking about the person they liked, and I wondered why I never could do the same. I wondered ‘why do I have feelings of attraction to women?’ I could never confess my feelings like everyone else. It was very frustrating not expressing my feelings. I desperately wanted to tell my friends who I liked but was afraid that they would deride me and spread rumors. I searched the internet to learn about my attraction to women and found the terms, ‘same sex love’ and ‘forbidden love’. When I saw ‘forbidden love’ I questioned whether I was a bad person.”

Searching the internet, Imai found a message board site for lesbians, and thought it was possible to find someone to confide in. “I discovered that I was not alone and that there were other people like me; I made an effort to find someone I could be friends with.” Eventually Imai found a friend and confidant. “I told her about my inability to talk about my attraction to women or people I liked. She responded that, ‘it is not necessary to directly say to a person that you like them; if you have consideration for each other you will naturally connect. Even without words it is important to feel happy together.’ Her words helped me immensely.”

5. The desire to be with someone

“When I had my first date at 19 it was a woman I met on an online messaging board. I had gotten along well with other women before, but they left once they knew I was Deaf. She said that it didn’t matter whether I could hear or not. I was really happy about that.” In the beginning Imai thought that meeting someone via the internet would be dangerous, but felt better after corresponding. When they met they naturally began dating. She was a pretty, feminine person who was good at dressmaking. They had a good time communicating through writing, but there were still communication problems. “When it was necessary to communicate while on a drive, messages had to be passed during traffic signal stops. It wasn’t possible to look at the view while communicating. She tried to learn sign language but never was fluid and conversations never went as expected. After two and a half months we broke up because of the difficulty communicating. It was nerve-wracking and tiring. My first relationship was a joy, but I believe that if we had used sign language the relationship would have been stronger.”

6. Imai’s path to becoming a filmmaker

“In the sixth grade I made a short film with my brother in which a hero and villain confront each other. It was a story I dreamed up myself that I filmed in our home and around our neighborhood. There were five characters, and my brother played all of them, including the villain.” (laughs) “My brother loves play-acting so was happy to do it. “In the 7th grade Imai showed the film to a Deaf teacher. “The teacher liked it and wanted to show it to the whole school. This experience inspired me to create films that can be enjoyed through sign language.” There were few films that could be enjoyed by Deaf audiences; films lacked subtitles and even when available, they could be difficult to follow. Also the educational philosophy of Oralism negatively affected the Japanese literacy of the deaf. “I suddenly desired to make people happy with films in sign language.”

In the 10th grade Imai entered a film in the Yokohama Deaf film festival and was awarded a prize for best film. “At that time I learned about a Deaf female director. Although I wanted to be a movie director, until I learned about her, I thought it would be practically impossible to become one. I decided to study filmmaking in university despite not liking studying so much.”

Imai studied in the University of Wako Faculty of Expression. Imai studied theater, costume, screenplay writing, movie production and set building. As a junior in a video seminar Imai made a film with classmates. Although there was support from other students through note-taking, much of the class content could not be covered by notes. “I perhaps learned half as much as the other students.” Although Imai tried to communicate through lip reading, effective communication was difficult. “The inability to communicate caused a lot of stress. In my first semester I usually ate lunch alone. Although I wasn’t sad, I would sometimes cry and realize that I had built up a lot of stress. I couldn’t understand all of the lectures or communicate well so my university life was frustrating and unsatisfactory.”

7. The desire to learn more about sign language

Imai wanted to make films that could be enjoyed by Deaf audiences, so making films necessitated the use of sign language. Imai also wanted to learn more about sign language. At that time Imai learned about the Japan Foundation Asia Pacific sign language linguistics dissemination and dictionary making project. “It was a program that allowed me five years to study sign language linguistics at the research center for Deaf studies in Hong Kong.” Japanese has the vowel sounds “a, i, u, e, o” and similarly sign languages have the discrete components of handshape, location, movement, orientation and non-manual markers to distinguish words. “A sign can have a different meaning simply by changing the orientation of the hand. If a single component of the sign is lost, communication is not effective and comprehension can be lost. In Hong Kong I learned JSL and HKSL while learning about linguistics. I was extremely happy to have the opportunity to study using sign language as the medium because I could really learn the content in a way that I could not as a university undergraduate.”

8. On sharing one’s gender identity

“When I started university I began living alone, and I came back home to visit after some time. My brother told my parents about his girlfriend, so I took the opportunity to tell them that I had a girlfriend too. My father did not seem surprised. He said that he had always believed that I liked women because during junior high school he had found an LGBTQ dvd in my room. He said I should have told them earlier, but he still wanted me to marry so he could have a grandchild. I told him that was impossible. Although my father was disappointed at the time, in 2017 he came to my Out in Japan exhibit. I didn’t tell him about the event but he heard about it somehow. He took a picture with my portrait as a background and sent it to me. In the photo he was smiling and looked extremely proud. My father’s acceptance of my gender identity made me very happy. After the Out in Japan event, it has been much easier to talk to my parents about my relationships.”

“When I told my friends that I was a lesbian, many accepted me, but there were those who responded negatively or or avoided me. It will still be some time before such people understand LGBTQ issues. The Deaf world is really small so there are more hurdles than in the hearing world, I suspect. Initially it was difficult but it allowed for discussions with people who also worried about their sexuality. I would identify those that I thought I could trust and tell them first.”

9. Neither male nor female

When Imai identified as lesbian some friends distanced themselves. “I found the people who really understood me. I don’t exclude people who don’t like me and I don’t mind if they leave. They don’t like it because they don’t understand what it is to be LGBTQ. Because I have suffered a lot, I don’t hurt people and try to treat others with kindness. That is my strength and many people who understand me like me for this quality. Once someone I was dating said, ‘We’ll never be able to marry will we?’ In order to marry the person I loved, I actually worried that I would have had to become a man.” Becoming a man would require surgery and hormone treatment and be very expensive. “I could have become a man and married my girlfriend but it would have been incredibly difficult to continue making movies. Ultimately, rather than becoming a man I wanted to concentrate my finances on filmmaking. My current partner is like family and accepts me as I am, so I am truly grateful. I have the body of a woman but when asked on a form whether to choose male or female, I’d rather not choose. I am who I am.”

10. The power of cinema: Thoughts about creating movies

“For those who initially reject the Deaf or LGBTQ community, I want them to see my movies with the hope that they will change their mindsets. Even if their point of view does not shift, they would have benefited from being educated.” As an LGBTQ person or Deaf person Imai is a minority. “Although a person might reject me, I will not exclude them. If I respond negatively, I will reflect poorly on the Deaf or LGBTQ community and negatively affect other people who share my identities. People are free to express their own opinions, but if they allow people to inform them, they might change their minds. Someone who watched my film with their family was able to build up the confidence to share their gender identity with their parents. That person’s experience really made me reflect on the power of film.”

“The most important thing in filmmaking is reality. I want to show Deaf people as they really are, without embellishment. A natural presentation allows Deaf viewers to enjoy films without incongruity and hearers can learn more about the Deaf community and the importance of sign language. I would like the Deaf community to learn more about sexual minorities. We need to learn about each other and work together side-by-side.”

In 2019 Imai’s first long feature Until Rainbow Dawn premiered at the 27th Rainbow Reel Tokyo International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival. “Until then I only made films with the Deaf in mind; therefore, with signing and no sound. This is my first film with sound. With a soundtrack, both the Deaf and hearing can enjoy the film together.” The setting of the film is Imai’s home prefecture, Gunma. The film depicts the story of a Deaf protagonist who falls in love and is caught in situations and conflicts that she cannot share with others. It reflects a small Deaf world. “Even though she wants to identify as a sexual minority, she can’t. It’s really important to show how the Deaf social world affects the protagonist.”

The passion for filmmaking undergirds the motivation that keeps Imai focused and unbothered by distractions. Imai simply wants to make films that audiences enjoy watching. “If I didn’t know my purpose in life I would probably be miserable, distracted by what I thought people would say about me.” Passion is Imai’s strength.

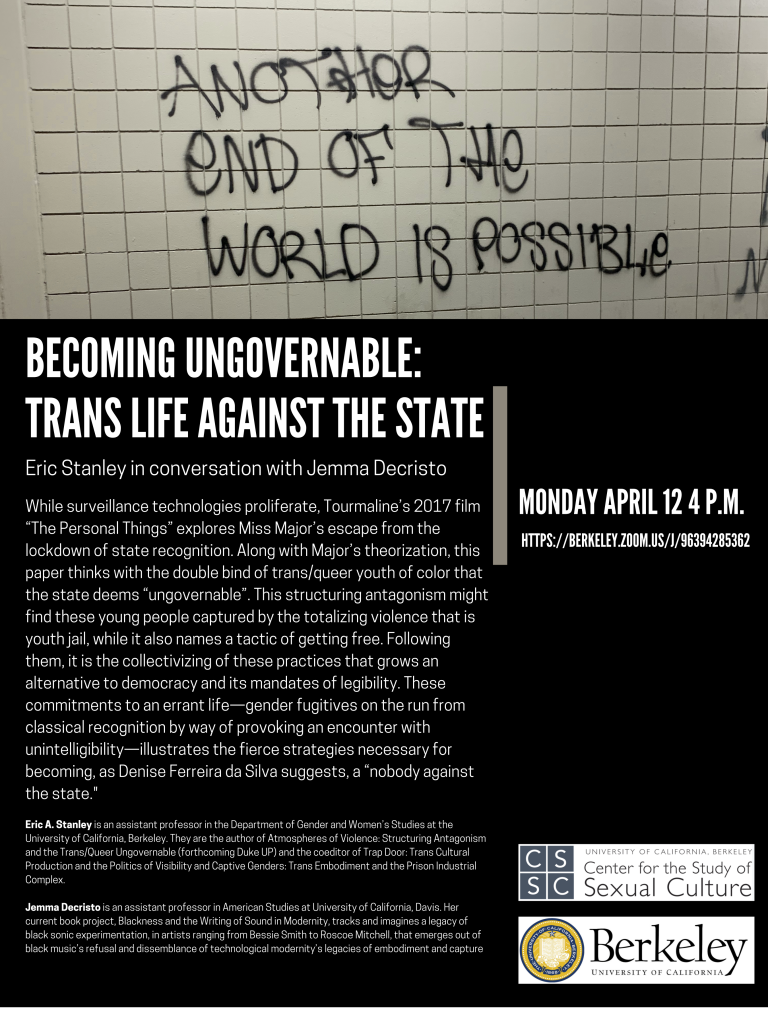

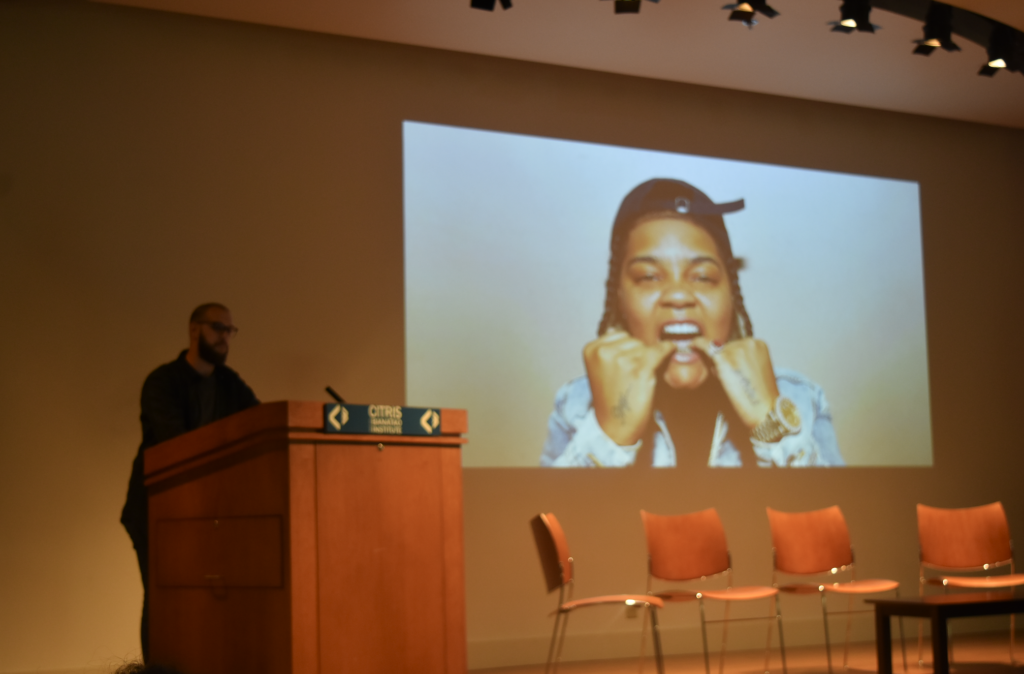

Eric Stanley, in conversation with Jemma DeCristo, delivers talk, “Becoming Ungovernable: Trans Life Against the State” (4/12)

Posted on June 22, 2021This past spring CSSC had the pleasure of hosting UC Berkeley professor Eric Stanley for their talk, “Becoming Ungovernable: Trans Life Against the State,” and conversation with Dr. Jemma DeCristo.

While surveillance technologies proliferate, Tourmaline’s 2017 film “The Personal Things” explores Miss Major’s escape from the lockdown of state recognition. Along with Major’s theorization, this paper thinks with the double bind of trans/queer youth of color that the state deems “ungovernable”. This structuring antagonism might find these young people captured by the totalizing violence that is youth jail, while it also names a tactic of getting free. Following them, it is the collectivizing of these practices that grows an alternative to democracy and its mandates of legibility. These commitments to an errant life—gender fugitives on the run from classical recognition by way of provoking an encounter with unintelligibility—illustrates the fierce strategies necessary for becoming, as Denise Ferreira da Silva suggests, a “nobody against the state.”

Eric A. Stanley is an assistant professor in the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. They are the author of Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonism and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (forthcoming Duke UP) and the coeditor of Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility and Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex

Jemma DeCristo is an assistant professor in American Studies at University of California, Davis. Her current book project, Blackness and the Writing of Sound in Modernity, tracks and imagines a legacy of black sonic experimentation, in artists ranging from Bessie Smith to Roscoe Mitchell, that emerges out of black music’s refusal and dissemblance of technological modernity’s legacies of embodiment and capture

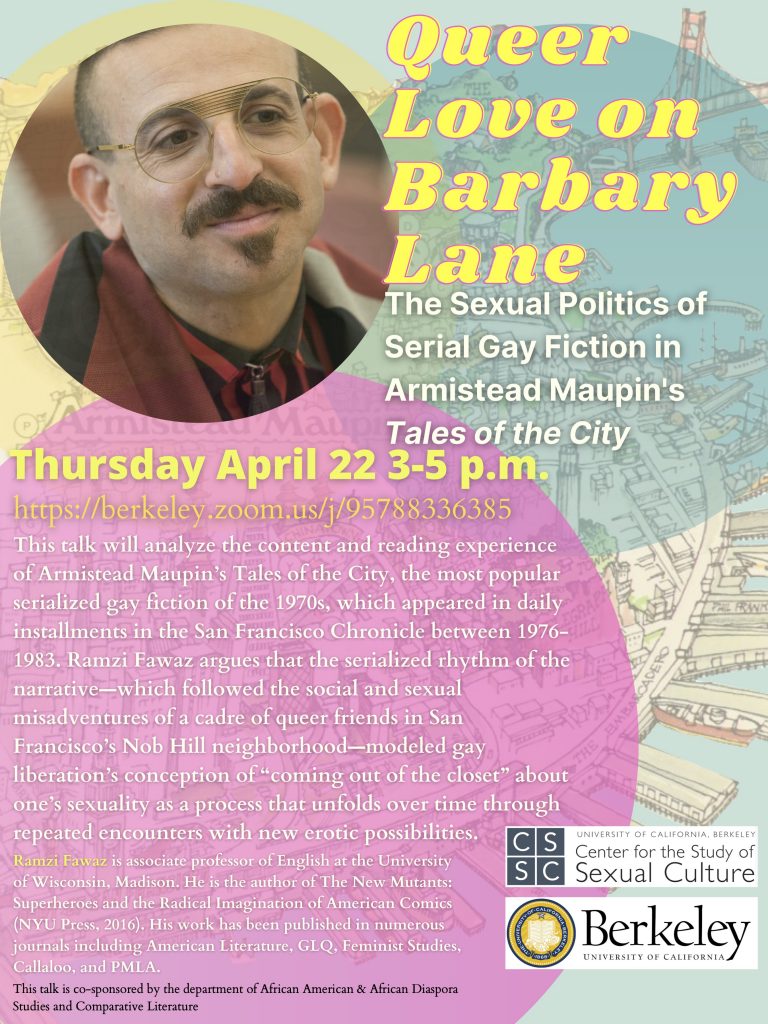

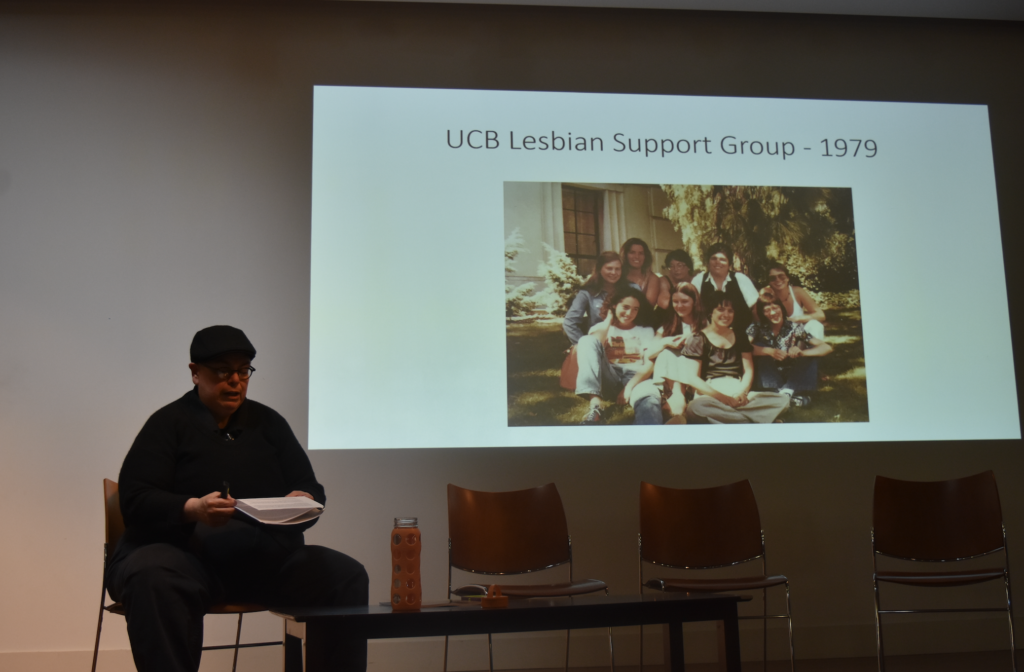

Ramzi Fawaz delivers talk Queer Love on Barbary Lane (4/22)

Posted onThis past Spring CSSC had the pleasure of hosting Ramzi Fawaz’s talk, Queer Love on Barbary Lane: The Sexual Politics of Serial Gay Fiction in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City.

If you would like to watch a recording of the talk, please email cssc@berkeley.edu.

Below is a description of the talk:

In this talk, I analyze the content and reading experience of Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the

City, the most popular serialized gay fiction of the 1970s, which appeared in daily installments

in the San Francisco Chronicle between 1976-1983. I argue that the serialized rhythm of the

narrative—which followed the social and sexual misadventures of a cadre of queer friends in

San Francisco’s Nob Hill neighborhood—modeled gay liberation’s conception of “coming out of

the closet” about one’s sexuality as a process that unfolds over time through repeated

encounters with new erotic possibilities. I draw upon interviews I conducted with actual San

Francisco readers of Maupin’s original text alongside close analysis of the rhetorical and literary

modes of address that Maupin deployed to make “coming out” a widely accessible form for

articulating one’s sexual and social desires, regardless of one’s specific sexual identity. I show

the story’s unfolding narrative about 1970s queer social life and the actual experience of

reading it daily alongside other San Francisco residents helped disseminate the radical sexual

politics of gay liberation to both gay and straight audiences alike.

Ramzi Fawaz is associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the

author of The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics (NYU

Press, 2016). His work has been published in numerous journals including American

Literature, GLQ, Feminist Studies, Callaloo, and PMLA. With Darieck Scott he co-edited a special

issue of American Literature titled “Queer About Comics,” which won the 2019 best special

issue of the year award from the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. His new book Queer

Forms explores the aesthetic and imaginative influence that movements for women’s and gay

liberation had on U.S.-American popular culture in the 1970s and after. Queer Forms will be

published by NYU Press.

This talk is co-sponsored by the departments of African American & African Diaspora Studies and Comparative Literature

#MeTooBehindBars: Trans/Queer Rebellion Across Prison Walls, Alisa Bierria and Rojas in conversation

Posted on October 31, 2020On Tuesday 10/27, CSSC had the pleasure of hosting a conversation between Rojas and Alisa Bierria. Scroll through for more information regarding our guests and the talk!

websites and organizations mentioned:

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/oct/08/prison-guards-abuse-california

https://wscadv.org/news/moment-of-truth-statement-of-commitment-to-black-lives/

http://defendsurvivorsnow.org/

https://www.survivedandpunished.org/

Rojas is a gender nonconforming, formerly imprisoned, survivor of violence. They organized against gender discrimination while serving a 15-year sentence at CCWF in California. They now organize with the Young Women’s Freedom Center, California Coalition for Women Prisoners, and #MeTooBehindBars, a campaign to end gender-based and sexual violence inside all women’s prisons in California.

Alisa Bierria is an assistant professor of African American Studies in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Riverside. She is also a co-founder of Survived & Punished, a national organization that challenges the criminalization of survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Cosponsored by the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies

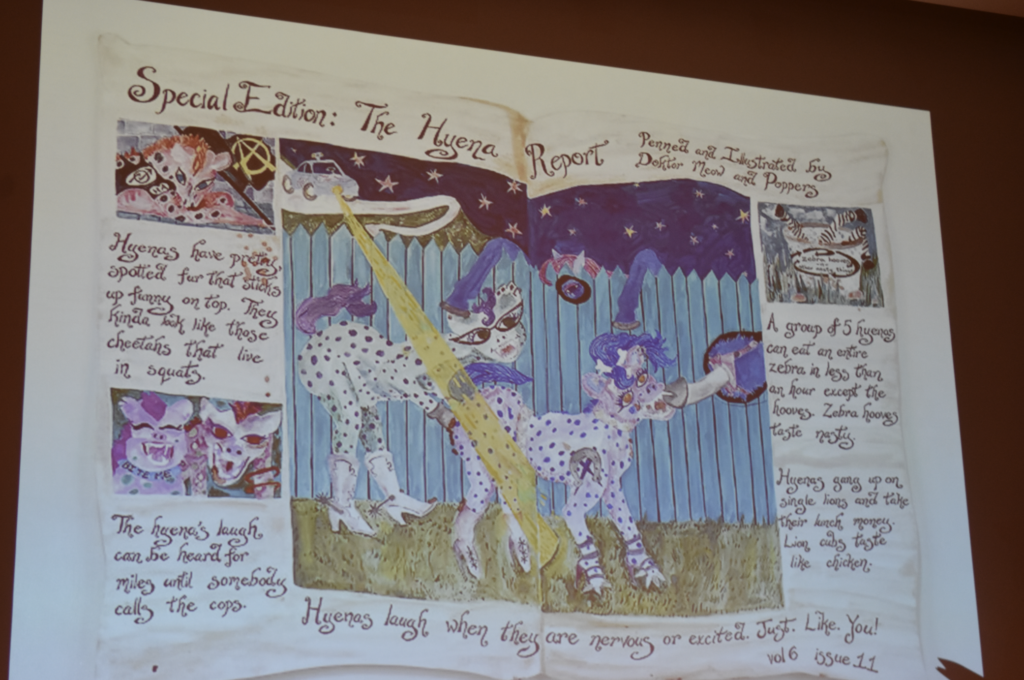

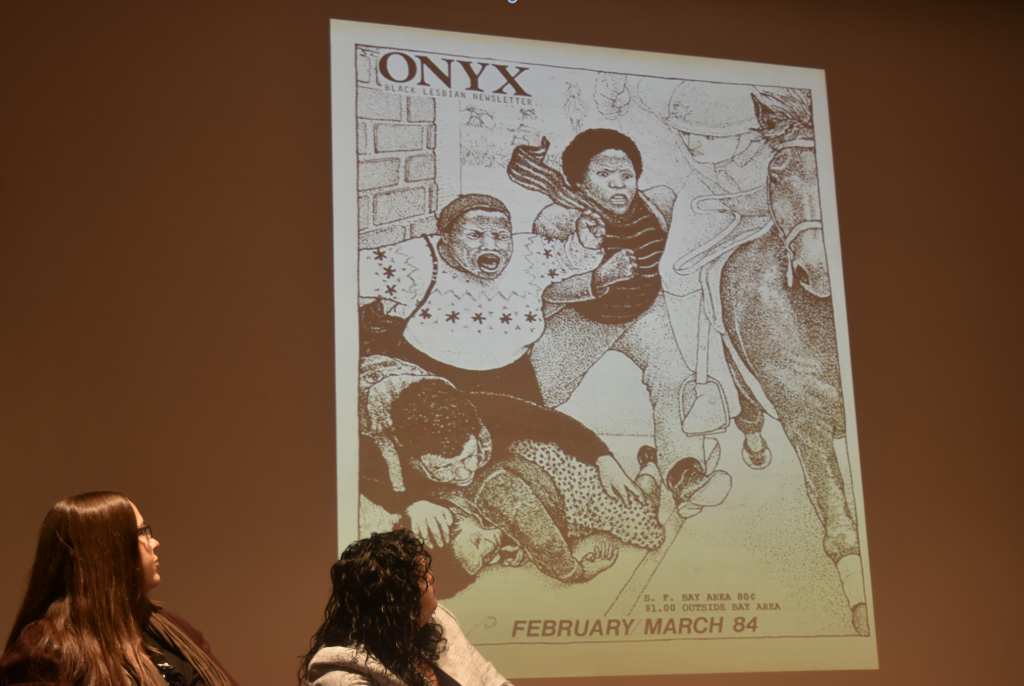

Reflecting on 2018 conference, Ev’ry Body This Time

Posted on September 24, 2020 From April 12-14, 2018, the Center for the Study of Sexual Culture hosted a conference titled “Ev’ry Body This Time,” which featured invited guest speakers like Qwo-li Driskill, Nayan Shah, Tracy Lee Bear, and others, as well as panels and workshops which sought to collaboratively imagine the future, answering the conference’s ultimate call: What future do “we” want looking forward from where we stand?

From April 12-14, 2018, the Center for the Study of Sexual Culture hosted a conference titled “Ev’ry Body This Time,” which featured invited guest speakers like Qwo-li Driskill, Nayan Shah, Tracy Lee Bear, and others, as well as panels and workshops which sought to collaboratively imagine the future, answering the conference’s ultimate call: What future do “we” want looking forward from where we stand?

This call and challenge was of course reflected on the conference’s title itself. The elision in “ev’ry” gestures in multiple ways: to the bodies that have been exempted in various iterations of sexuality studies, and to our quixotic desire to (re-)emplace them. It refers as well to the shifting and ever-proliferating fact of bodies: the way that apparent gaps may not represent incompleteness, but point instead to troubled standards of perceiving or evaluating wholeness; that filling a gap can thus provisionally flesh out bodies that are at once legible and illegible. Race and gender, in their mutable complexities, sit at the core of these questions. Our apostrophe calls to a multitude of bodies, recognizing the potential for thinking through, substituting, re-visioning, and, ultimately, holding space for, bodies that exceed categorical legislation and rhetorical disciplinarity. We also note that embodiment is not everyone’s cup of tea. We flag the body, ev’ry body, because sensuousness has too often been left out of considerations of sexuality and politics. Simultaneously, we wonder how given languages about sex and meaning work in relation to disability, debility; in the realm of the digital; under the aegis of asexuality? “This time” means both that we view this as a conference that belongs to a history of academic conferences in queer studies and that we view this as a conference that happened in a perilous present moment. How is the critical study of sexuality evolving and in response to what imperatives? What is the relation of this time to other times (and places) and how are the particular urgencies of this time tied to other moments? Is the critical study of sexuality always explicitly about sexuality, now?

The speakers, panelists, and guests took on this invitation to think critically through an array of topics and issues, ranging from notions of embodiment and pleasure to issues of temporality and spatiality. Scroll through for videos and photos of the conference!

Join the CSSC Mailing List

Posted on September 24, 2014The CSSC has started a mailing list. To find out about upcoming CSSC events, subscribe here.

New CSSC website

Posted on September 3, 2014 The CSSC is pleased to launch its brand new website! After a hiatus, the Center has been reopened under new Director Mel Chen, Associate Professor of Gender & Women’s Studies. The Fall 2013—Spring 2014 year was spent largely reorganizing and rebuilding the Center’s programs, and this upcoming Fall 2014—Spring 2015 year will offer a full schedule of CSSC-sponsored events, including our monthly Speaker Series, co-sponsorships of a variety of conferences, symposia, and screenings, and meetings of the CSSC-sponsored Queer of Color Working Group. Check our Events page for an up-to-date calendar. Special thanks to our web designers Stefan Gutermuth and Colin Frangos, and to Toronto artist Elisha Lim, who provided the illustrations.

The CSSC is pleased to launch its brand new website! After a hiatus, the Center has been reopened under new Director Mel Chen, Associate Professor of Gender & Women’s Studies. The Fall 2013—Spring 2014 year was spent largely reorganizing and rebuilding the Center’s programs, and this upcoming Fall 2014—Spring 2015 year will offer a full schedule of CSSC-sponsored events, including our monthly Speaker Series, co-sponsorships of a variety of conferences, symposia, and screenings, and meetings of the CSSC-sponsored Queer of Color Working Group. Check our Events page for an up-to-date calendar. Special thanks to our web designers Stefan Gutermuth and Colin Frangos, and to Toronto artist Elisha Lim, who provided the illustrations.